Why we can't forget things that never happened

SO many villages and towns around Britain have a story so good it would definitely benefit from what I would tentatively call a "Black Plaque" scheme.

If English Heritage's little blue signs are intended to single out sites with links to celebrated historical figures, the Black Plaque - by contrast - would be the benchmark for folklore.

"It was on this spot the people of Woolpit greeted the Green Children in the reign of King Stephen" or "In this place Spring-Heeled Jack caused a coach to crash in 1837."

I can't imagine the idea would take off in the corridors of Whitehall but what's interesting is the way that local communities themselves often embrace old folk stories in the knowledge that, centuries on, it's still very much their thing.

Let's take Bungay in Suffolk, a small market town which even today scarcely has 5,000 people living there.

Here in an August storm of 1577, a gigantic black dog was said to have manifested in the middle of the parish church - striking two of the congregation dead and scorching the door on his way out.

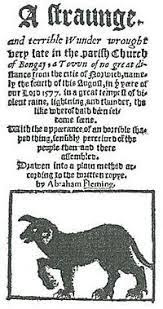

Depending on who - or what - you believe, the infamous episode was probably the best-known appearance by the hellhound Black Shuck, an attempt by god-fearing villagers to understand the rare occurrence of ball-lightning or a plumb publishing opportunity for London clergyman Abraham Fleming - whose contemporary pamphlet "A Strange and Terrible Wonder" helped immortalise the story.

Regardless of your thoughts, almost 450 years on it is more than just the woodwork of St Mary's Church which bears the marks of the strange tale.

The weathervane which caps a lamp post in the heart of the town is fashioned in the shape of the Black Dog.

The same beast appears on the town's coat-of-arms and lends its name to everything from a nearby ladieswear shop to the local football team. It is interwoven in the community's history in just the same way a famous poet or Civil War skirmish might be.

"Ah but that's rural East Anglia," you might think. "It's a town no-one's heard of in a part of the country not really on the way to anywhere in particular, they need an angle don't they?"

But consider then the case of Coventry, a bustling city at the very heart of the nation and with a population more than 100 times that of Bungay.

I was struck during my days as a local government reporter that the local council had chosen as its insignia not the cathedral - whose Medieval ruin still stands as a testament to the horrors of The Blitz - but the far more ancient image of Lady Godiva. That woman, whose naked jaunt on horseback, which most historians are convinced never took place, is stamped on every local authority letterhead and planning agenda

These examples demonstrate that it doesn't actually matter whether an extraordinary incident happened, but rather that enough people are familiar with what is said to have happened for the story still to matter centuries on.

Nor is the effect always purely local. At one time or another the fearsome beast which haunted Suffolk's byways and backwaters entered the national psyche. A similar creature in Dartmoor inspired Arthur Conan-Doyle's Hound of the Baskervilles, while Winston Churchill himself was known to compare his sporadic bouts of depression with a black dog...

The continued resonance of folklore is partly why I've always been so fascinated by the topic, instinctively feeling that it's much closer to more traditional disciplines like history and psychology than most people care to realise - or admit.

It's also why I loved Rhianna Pratchett's recent Radio 4 series on Britain's mythical creatures, which attempted to consider why such stories came into being, how they've evolved and how we understand them today.

Comments

Post a Comment